Alcyone and Pleiades Talismans

In Greek legend they were known as the Seven Daughters of Atlas and Pleione; Alcyone, Celano, Maia, Merope, Taygete, Asterope (called the storm-pleaid) and Electra. The ancient Greeks referred to the Pleiades as the ‘sailing stars’ and designated their Oceanid mother Pleione the ‘sailing queen.’ In the origin story of how they became stars, Orion saw the seven sisters dancing and consumed by lust tried to capture them. The sisters cried out to Zeus to protect them and he turned them into doves, placing them in the sky. This story shares many similarities with Aboriginal Australian legends in which the Pleiades are often interchangeably described as female birds and women who are pursued by males, like the seven emu women who are chased by dingo men in the story of the Magara.

The stars of the Pleiades form Krittika, the third Nakshatra in Vedic Astrology. Ruled by Agni, the god of sacred fire and transformation, Krittika embodies immense willpower, determination, and tenacity. Krittika translates to "the cutters" and is known as the “star of fire.” It is symbolized by the flame and the blade, representing the power to burn and slice away the profane, revealing hidden and buried truths. Through Krittika’s fires of purification, we are renewed, and the spark of divinity is ignited.

The Making of the Alcyone and the Pleiades Talismans

When I first conceptualized the creation of the Pleiades talismans, the lyrics “Give me your eyes so I might see / the blind man kissing my hand” from The Cure’s song Strange Day resonated in my mind like a brainworm, a foreshadowing that set the tone for this working; a riddle in a song with the theme of sight and blindness. The Pleiades have long been associated with both sight and the spirit realms. Within the traditions of astrological magic, they are revered as one of the 15 magical Behenian stars, known to aid practitioners in acquiring spirit sight, occult knowledge, and spirit contact.

The wax carving for these talismans commenced just before the cross-quarter day known as Beltane. Initially, I spent several days working with the wax in a blind, exploratory manner, allowing the possibility of a new image to emerge. Ultimately, I adhered to grimoire tradition, choosing to create a Lamp, the image associated with the Pleiades as found in the Bodleian manuscript and later by Agrippa:

"Under the constellation of Pleiades, they made the image of a little Virgin, or the Figure of a Lamp; it’s reported to increase the light of the eyes, to assemble Spirits, to raise Winds, to reveal secret and hidden things."

Throughout the spring cross-quarter period, I dedicated many days to meticulously carving and forming the wax piece. This period, characterized by the thinning veil between worlds and the verdant eruption of life, proved to be an ideal time for such a meditative process. As the aforementioned song continued to echo in my thoughts, I decided to inscribe the first line, “give me your eyes so I might see,” in Greek:

Δώσε μου τα μάτια σου για να δω

This phrase was carved into the back of the talisman, erased, and re-inscribed two more times, each iteration contributing to the talisman’s final form. Ultimately, I placed the sigil for The Pleiades over the area where the words had been inscribed, effectively sealing them. I then chose to incorporate a fire motif emerging from the Lamp, housing the quartz gemstone designed in an organic yet filigree style inspired by Art Nouveau.

The fire feature of the talisman wasn’t pre-planned; it emerged organically through the meditative process of creation. I spent days carving and shaping, and at one point, as I was working, I noticed a dragon beginning to take form within the organic shapes. Intrigued, I decided to refine it further. The unexpected emergence of this dragon was both surprising and exhilarating, presenting me with the challenge of understanding and refining this unplanned element.

In my work, I strive to let the creative process lead, while also grounding my practice within a research-based framework. In the academic arts, this approach is known as practice-led research, a methodology that centers and elevates the artist's creative practice as a legitimate form of research. This was one of the key insights from my Master of Fine Arts degree, and it continues to shape the way I approach my art. Through this method, the process of creation itself becomes a form of inquiry, where unexpected discoveries—like the dragon within this talisman—can lead to new insights and directions.

Smith and Dean, in Practice-Led Research, Research-Led Practice in the Creative Arts, explain that "the product of creative work itself contributes to the outcomes of a research process and contributes to the answer of a research question. Creative practice—the training and specialized knowledge that creative practitioners have and the processes they engage in when they are making art—can lead to specialized research insights which can then be generalized and written up as research."

I include this to highlight how I approach my art, magical practice, and witchcraft, especially when something unplanned and unexpected arises. In this case, the creative process itself guided and informed my research. Immersed in the mythology of the Seven Sisters, I felt compelled to switch gears and embark on a seemingly impossible quest: uncovering dragon and serpent lore connected to the Pleiades.

As luck would have it—or should I say the spirits—the information I was seeking came to me within a few days when I found myself in a chance conversation with Katarina Pejović, who shared with me about her work focused on the Zmaj dragons and serpents of Balkan folklore. In passing, she mentioned their connection to the Pleiades. After I shared my experiences with crafting the Pleiades talisman, Katarina generously shared two Balkan folk stories about the Pleiades serpents, which she has given permission to include. For those interested in a deeper exploration, I highly recommend her booklet Balkan Folk Magic: Zmaj, released through Haedan Press, which provides an in-depth look at the Zmaj dragons and serpents.

From Katarina Pejović:

“The first story is translated as ‘The Serpent Bridegroom’ and exists in numerous versions throughout the Balkans. It can be found online in various collections of translated folk tales recorded by Vuk Karadžić. In short, the tale begins with a queen who is unable to conceive and prays to God for a child, saying, ‘even if it ends up being a serpent.’ In time, she indeed gives birth to a serpent (in these stories, the term ‘zmija’ is often interchangeable with ‘zmaj,’ as dragons and divine serpents are seen as one and the same as the stars themselves). As the serpent grows older, he seeks a wife and eventually marries a young woman who promises to love him regardless of his form.

When the woman becomes pregnant, her mother-in-law, the serpent’s own mother, becomes increasingly curious about the miracle of her pregnancy. After persistently questioning the young wife, she finally learns that her son has a human form—indeed, he is the handsomest youth in the land—which he reveals only to his wife at night when he sheds his serpent skin. Obsessed with discovering her son’s true appearance, the mother-in-law convinces the young wife to hide the serpent skin the next time he sheds it so that she can see him in his human form and cast the skin out the window of their room in the castle.

When the serpent’s wife throws away the snakeskin, her mother-in-law, instead of hiding it, burns it in a pyre, hoping to force her son to remain human. However, following much of the lore surrounding spirit lovers, this act becomes a token of divorce, banishing the serpent from physical incarnation. The serpent’s wife is devastated and begs for forgiveness, but as he fades from this world, he tells her that she will be unable to give birth to their child without his touch and that she must journey through the skies with shoes and a staff made of meteorite to find him.

Determined to reunite with him, the serpent’s wife embarks on a shamanic journey through the sky. With the aid of her meteorite shoes and staff, she flies in spirit to the Mother of the Sun, who takes pity on her and reveals that while her son, the Sun Himself, has not seen her husband during the day, the Moon might have. Before she departs, the Mother of the Sun grants her a golden loom and thread. This journey repeats with the Mother of the Moon, whose son has not seen the husband during the night, but she gives the wife a golden hen with golden chicks. Finally, the Mother of the Wind directs her to another kingdom where her husband has reincarnated, giving her a golden feather cloak. The Wind blows her to this new realm, where her shoes and staff shatter, fixing her in this foreign land.

In this world, she discovers that her husband has been tricked into marrying a new empress, a witch who seeks to use his power as an anchor to this world through their marriage. Though the empress desires the serpent’s endless power, her loyalty lies more with her own greed. Our protagonist hatches a plan to win him back.

She offers all her golden gifts, except for her cloak, in exchange for spending a night with the king—a deal the witch eagerly accepts. However, each night, the witch gives the serpent a sleeping potion, preventing his first wife from communicating with him as she pleads for his forgiveness.

On the third night, when she is to trade away the cloak—the most coveted of her gifts—the serpent (in his human form) is warned by one of his guards that he has been ‘sleeping with another woman’ for the past two nights, who has been crying and pleading for him to wake up. Suspecting the witch’s involvement, he hides a sponge in his mouth to absorb the potion.

At last, on the final night, the serpent remains awake. Hearing his wife’s cries, he tearfully accepts her apology and embraces her; his touch releases the curse, allowing her to instantly give birth to their son—a golden-haired, golden-eyed half-dragon (zmajevit) hero. In many versions of the story, it ends here with the couple returning to their world. However, in my favorite retelling, there is one final element: the wife begs the serpent to return home, but he reminds her that without his serpent skin, he cannot take his mythic form and return to their realm as an incarnate being. Instead, the wife places her golden feathered cloak over his shoulders, and as it adheres to his skin, he transforms into a massive golden dragon. With their son in her arms, she mounts him, and they fly back to the incarnate world together.

In some versions of the story, their child becomes the first of seven who form the Pleiades, or the first of five, with the husband and wife becoming two of the seven stars. This mirrors another famous dragon-related story known as ‘The Seven Little Vlachs,’ a nickname for the Pleiades. In this tale, a human hero becomes the adopted brother of five half-dragon (zmajevit) brothers through their mother, an elderly dragon bride. Together, they rescue a princess from a seven-headed dragon (a tyrannical serpent seeking to marry her non-consensually), and then they argue over who will marry her. Seeking advice, they consult the Mothers: the Mother of the Wind suggests they seek the Mother of the Moon, who recommends the Mother of the Sun. Finally, the Sun’s Mother advises them to ask their own Mother. The elderly dragon bride resolves the matter by adopting the princess, ensuring that all seven become siblings. It is said that during Orthodox St. George’s Day (May 6) and St. Vitus’ Day (June 28), the Seven Little Vlachs—the Pleiades, consisting of the five dragon brothers, the young man, and the princess—are absent from the sky because they return to the Mothers in their realms to thank them for their advice.”

Everything about these stories resonated deeply with me. What could be more enchanting than dragons and serpents taking their place among the stars as the Pleiades, and meteorites serving as tools for spirit flight? Katarina explained that in Balkan folklore, it is common for a female sorceress or a serpent’s bride to craft shoes and a walking staff from meteorites to visit the Pleiades or the Houses of the Mothers of the Sun, Moon, and Wind—three significant goddesses in folk magic. She also shared that meteorites are considered dragons in themselves by the Balkan people, as they are believed to fall to earth as meteorites and lightning bolts.

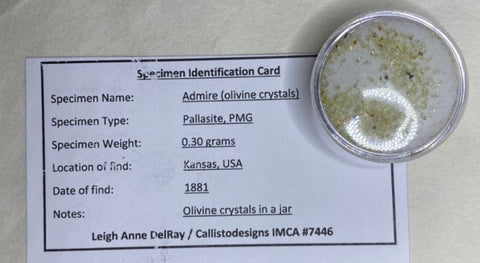

My fascination with meteorites quickly grew, and my interest in gemology led me to delve into their different subtypes and chemical compositions. I discovered that the most common mineral in meteorites is iron, followed by olivine. While iron is the first thing that comes to mind when we think of meteorites, olivine is less familiar. It is a silicate mineral composed of iron and magnesium, notable for its crystal structure. When an olivine crystal reaches gem quality, it is known as peridot or chrysolite—a gemstone that radiates a brilliant green.

The Gemological Institute of America calls peridot the “extreme gem,” as it is born of fire and brought to light. Unlike most other crystals formed in the earth’s crust, peridot (along with diamond) originates in the molten rock of the earth’s mantle and is brought to the surface by the immense forces of earthquakes and volcanoes. Scientists have determined that the earth’s upper mantle is composed primarily of olivine, much of which is likely peridot. Upon learning this, I had the vision of a magnificent Emerald Palace deep within the earth—made not of emerald, but of peridot.

The pallasite meteorite is a unique type of meteorite that contains peridot and iron in a matrix-like structure, resembling snake skin. Inspired by the folktales of sorceresses using meteorites to assist in spirit flight—to ascend and visit the celestial realms—I decided to acquire some for myself. I collected several samples, including a specimen container of tiny peridot crystals from the Admire meteorite, which I used in these talismans.

While my interest in meteorite dragons and serpents was sparked by Balkan Zmaj folklore, I have since discovered similar tales and evidence from ancient cultures around the world. One notable example is the Aboriginal people of Australia, for whom meteors are often associated with serpents. One of the world’s largest meteor impact sites, known as Wolfe Creek Crater, is located in the outback of Australia. The crater, measuring 850 by 900 meters in diameter, is estimated to be 300,000 years old. The Djaru people, who inhabit the area, refer to this structure as Kandimalal. I found several stories related to this crater in an article from Archaeoastronomy: The Journal of Astronomy in Culture.

One story tells how one night, the moon and the evening star passed very close to each other. The evening star became very hot and fell to the earth, causing a brilliant, deafening explosion. This greatly frightened the Djaru and it was a long time before they ventured near the site, only to discover it was the spot where the evening star had fallen. Goldsmith reports that the Aboriginal Elder told him this story came from his grandfather’s grandfather, indicating it was handed down in its present form before the scientific identification of the crater. A Djaru Elder named Jack Jugarie (1927-1999) gave his account of the Wolfe Creek crater: “A star bin fall down. It was a small star, not so big. It fell straight down and hit the ground. It fell straight down and made that hole round, a very deep hole. The earth shook when that star fell down”

Speiler Sturt, a Djaru Elder from Billiluna, Western Australia, also illustrates the cosmic origins of Wolfe Creek crater: “That star is a Rainbow Serpent. This is the Aboriginal Way. We call that snake Warnayarra. That snake travels like stars travel in the sky. It came down at Kandimalal (Wolfe Creek). I been there.”

Rainbow Serpents are the primordial creator deities of the Aboriginal people, often depicted as giant, rainbow-colored flying serpents. In a popular Dreaming story from Cape York, which has been adapted into a children's book, the Rainbow Serpent Gooriala is said to have shaped the landscape. When Gooriala eventually leaves the land, he is seen flying through the night sky as a shooting star.

If we revisit the passage on the Pleiades in Agrippa, particularly the line "to increase the light of the eyes," we can uncover an etymological connection to serpent and dragon lore. To increase the light in the eyes is to become sharp-sighted. The ancient Greek word “Δράκων” (drakōn) for dragon literally translates to "sharp-sighted" and is traditionally related to “δέρκομαι” (derkomai), meaning ‘to see.’ Throughout history, serpent deities and spirits have been revered as keepers of mysteries and secret knowledge.

In The Three Books of Occult Philosophy, Agrippa outlines the process for creating Behenian Fixed Star talismans by selecting the herb and gemstone associated with the star and setting the gemstone into a ring or pendant at an elected time, with the herb placed beneath. For these talismans, I chose fennel as the herb and a cabochon crystal quartz as the gemstone, following Agrippa's guidance that the gemstone for the Pleiades is crystal (quartz) and the herb is fennel.

Fennel is native to the Mediterranean and was highly valued by the ancient Greeks and Romans, who used it for both medicinal and culinary purposes. Fennel tea was believed to give courage to warriors before battle, and according to Greek mythology, Prometheus used a giant stalk of fennel to bring fire to humankind. Fennel is also one of the three main herbs used in the preparation of absinthe, an alcoholic spirit known for inspiring visions and dream-like states.

Fennel is native to the Mediterranean and was highly valued by the ancient Greeks and Romans, who used it for both medicinal and culinary purposes. Fennel tea was believed to give courage to warriors before battle, and according to Greek mythology, Prometheus used a giant stalk of fennel to bring fire to humankind. Fennel is also one of the three main herbs used in the preparation of absinthe, an alcoholic spirit known for inspiring visions and dream-like states.

Additionally, Pliny the Elder noted fennel's benefits for eyesight, particularly in relation to serpents. He explained that serpents use fennel to stimulate the shedding of their skin and to sharpen their vision in the spring, drawing the conclusion that what benefits the serpent must also benefit humans:

"The snake, when the membrane which covers its body has been contracted by the cold of winter, throws it off in the spring by the aid of the juices of fennel, and thus becomes sleek and youthful in appearance. First of all, it disengages the head, and it then takes no less than a day and a night in working itself out, and divesting itself of the membrane in which it has been enclosed. The same animal, too, on finding its sight weakened during its winter retreat, anoints and refreshes its eyes by rubbing itself on the plant called fennel."

Fennel became famous due to the serpent's use of it, as they consume it to shed their old skin and sharpen their eyesight with its juice. This led to the belief that fennel juice is highly beneficial for human sight as well. Fennel juice is gathered when the stem is swelling with the bud, after which it is dried in the sun and applied as an ointment with honey.

In addition to the techniques outlined by Agrippa, I also employed those of Ficino, as conveyed in Three Books on Life. Ficino explicitly states that it is the hammering and heating alone that activates and manifests the latent power within the material (metal):

"This hammering and heating, if it happens under a harmony similar to that celestial harmony which had once infused power into the material, activates this power and strengthens it as blowing strengthens a flame and makes manifest what was latent before, as the heat of a fire brings to visibility letters previously hidden which were written with the juice of an onion; and as letters written with the fat of a goat on a stone, absolutely unseen, if the stone is submerged in vinegar, emerge and stick out as if they were sculptured. Yes, and just as the touch of the broom or the wild strawberry excites a dormant madness, then perhaps hammering and heating alone brings out the power latent in the material, if it is done at the right time."

I chose the heliacal rise (first visibility) of Alcyone at my location and conducted this work over three elected windows, which occurred between 4-5 am each day, beginning on June 19th and culminating on the morning of midsummer, the summer solstice. During the first election, I placed fennel and Admire meteorite crystals beneath the crystal quartz cabochons and hammer-set the quartz. In the next election, I completed the back, where I had created a setting for a mati (evil eye charm) that serves as a door to a cavity within the talisman. I filled the cavity with fennel seeds and a small piece of meteorite before setting the mati on top. On the final day, I performed the final invocations.

After completing the election, I turned to Carl Jung’s Red Book for bibliomancy and opened it to this artwork created by Jung:

In this artwork, we see a figure pouring the Aquarian life-waters onto a green, lizard-like dragon lying on the earth. From the dragon, seven flowers emerge, and atop these flowers are the Kaberoi, a group of enigmatic chthonic deities. The Kaberoi were worshiped in a mystery cult closely associated with Hephaestus. In Greek mythology, the Cabeiri are generally identified as divine craftsmen, considered to be the sons or grandsons of Hephaestus.

I am delighted to have Sasha Ravich contribute the rite The Mantic Milk of the Emerald Palace to accompany these talismans. Sasha deeply understood this work and has crafted a Stellar Witchcraft rite unparalleled in it's poetic beauty. The rite will be shared in each booklet that accompanies the talismans.

Excerpt from the rite:

"Listen closely, for we will only tell you once—you must remember that the way back is the way through, and going through means that there is no way back.

Listen closely, for we will only tell you once—there is a city beneath the crust of the frozen earth, there is a city fathoms deep in the sky.

Listen closely, for we will only tell you once—in this city, there is a palace made of emerald glass, iron, and olivine.

Listen closely, for we will only tell you once—in this palace, there is an atrium; in this atrium, there is a chalice.

Listen closely, for we will only tell you once—in this chalice, there is an elixir, and it is the most prized thing in the palace.

Listen closely, for we will only tell you once—this elixir is for Seeing True, seeing as We Do; it is a milk which glows green-flamed and bright.

Listen closely, for we will only tell you once—and if one washes their face in this unctuous broth, they too will possess our Serpent’s Sight."

The Alcyone and Pleiades talismans are hand-carved in hard jeweler's wax, cast in sterling silver, and set with a crystal quartz cabochon and a mati made of shell. Each talisman contains fennel seeds, rock and iron meteorites, and peridot crystals from the Admire meteorite. The talismans hang on a sterling silver chain and are presented in a silk-lined box.

View the Alcyone and Pleiades talismans

References:

Attrell, Dan, and David Porreca. Picatrix. A Medieval Treatise on Astral Magic. University Park, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019.

Brady, Bernadette. Star and Planet Combinations. Wessex Astrologer Ltd, 2008.

Eratosthenes, et al. Constellation Myths. Oxford Oxford Univ. Press, 2015.

Hamacher, Duane W., and Ray P. Norris. “Australian Aboriginal Geomythology: Eyewitness Accounts of Cosmic Impacts?” arXiv.Org, 22 Sept. 2010, arxiv.org/abs/1009.4251.

Harness, Dennis M. Nakshastras. Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 2004.

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa. Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Simon and Schuster, 23 Nov. 2021.

Jung, C. G., and Sonu Shamdasani. The Red Book = Liber Novus: A Reader’s Edition. W.W. Norton, 2009.

Kaske, Carol V. Marsilio Ficino, Three Books on Life: A Critical Edition and Translation. Medieval & Renais Text Studies, 1 Nov. 2019.

Pliny, and D. E. Eichholz. Natural History: With an English Translation, in Ten Volumes. Heinemann, 1962.

Roughsey, Dick. The Rainbow Serpent. Sydney, Nsw Angus & Robertson Publishers, 2011, first published 1978.

Smith, Hazel, and Roger T Dean. Practice-Led Research, Research-Led Practice in the Creative Arts. 30 June 2009.

White, Gavin. Babylonian Star-Lore : An Illustrated Guide to the Stars and Constellations of Ancient Babylonia. London, Solaria Publications, September, 2014.